This new semester begins for many Universities with a ‘scholar strike,’ an action to draw attention to the Black Lives Matter movement, but also to all forms of racism and the privilege that many Whites have in relation to others, referred to collectively as BIPOC. (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour). This strike is meant to be a continuation of the need to undo Indigenous invisibility, anti-Blackness, dismantle white supremacy and advance racial justice.

This new semester begins for many Universities with a ‘scholar strike,’ an action to draw attention to the Black Lives Matter movement, but also to all forms of racism and the privilege that many Whites have in relation to others, referred to collectively as BIPOC. (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour). This strike is meant to be a continuation of the need to undo Indigenous invisibility, anti-Blackness, dismantle white supremacy and advance racial justice.

Within research this can mean a number of things: listening to and learning about Indigenous research methodologies, reading research conducted by BIPOC, learning to talk, write, and review research in inclusive ways.

Indigenous methodologies

There is a growing body of literature on Indigenous research methodology, easily accessible through various search engines. Here, I want to simply introduce some initial thoughts about how an Indigenous research methodology may differ from other research methodologies.

Cora Weber-Pillwax suggests these basic principles that characterize Indigenous research methodology:

(a) the interconnectedness of all living things,

(b) the impact of motives and intentions on person and community,

(c) the foundation of research as lived indigenous experience,

(d) the groundedness of theories in indigenous epistemology,

(e) the transformative nature of research,

(f) the sacredness and responsibility of maintaining personal and community integrity,

(g) the recognition of languages and cultures as living processes.

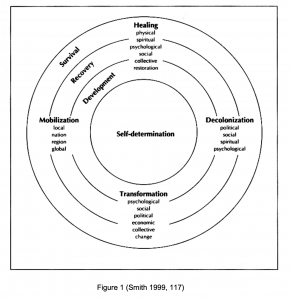

An Indigenous research agenda might look something like this:

Indigenous Epistemology

As with all research, presumptions about knowledge (epistemology), reality (ontology), and values (axiology) are foundational. In general, discussions of these foundations has been couched in long standing Euro-centric views. Even though many views on interpretive and critical research may accommodate an Indigenous worldview (for example, a social constructionist epistemology privileges inter-subjectivity and human connection) most nonetheless are inadequate for fully capturing this way of seeing and being in the world.

Key aspects of Indigenous epistemologies are relationality (we are all related to each other, to the natural environment, and to the spiritual world, and these relationships imply interdependencies), the interconnection between sacred and secular, and holism (everything is related and cannot be separated, and thus wholes must be maintained for understanding)… what Weber-Pillwax calls the “interconnectedness of all living things.”

Notions of Indigenous pedagogy are intertwined in Indigenous epistemology as learning (knowledge sharing) occurs through the process of observing and doing, and by interacting over long periods of time with elders in a natural environment. This learning process is subtle and unobtrusive and in non-Indigenous eyes it may not even be recognized as learning.

There are a growing number of global resources to guide recognition, understanding and valuing Indigenous knowledge, including the Principles & Guidelines for the Protection of the Heritage of Indigenous People and Science for the Twenty-first Century. Most university libraries, including UBC, have relatively easy portals for accessing books, articles, and resources on Indigenous research methodologies. (UBC portal) See also, Marie Battiste’s literature review on Indigenous epistemology and pedagogy.

Anti-racist methodologies

There has been for some time a growing awareness of putting race at the centre of research projects, methodologies and theoretical approaches. Critical Race Theory asserts “racial inequality emerges from the social, economic, and legal differences that white people create between “races” to maintain elite white interests in labour markets and politics, giving rise to poverty and criminality in many minority communities. The CRT movement officially organized itself in 1989, at the first annual Workshop on Critical Race Theory, though its intellectual origins go back much further, to the 1960s and ’70s.” (Source) CRT as an orientation was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw and originated as a legal movement to challenge and shift race paradigms in the US.

Anti-racist research is generally situated within a critical research theoretical perspective given the focus on differential access to power for minoritized people seen through the lens of race, class, gender, and sexuality. Anti-racist research is not content with describing and understanding differences, but intends to understand, challenge and change values, beliefs and actions that sustain systemic racism.

Anti-racist research is generally situated within a critical research theoretical perspective given the focus on differential access to power for minoritized people seen through the lens of race, class, gender, and sexuality. Anti-racist research is not content with describing and understanding differences, but intends to understand, challenge and change values, beliefs and actions that sustain systemic racism.

Anti-racist research methodologies include critical ethnography, critical discourse analysis, critical narrative inquiry, and Indigenous research methodologies with attention to the relational aspects of research, that is, doing research with, not on, BIPOC.

Follow

Follow